Blockchain basics

Before diving deeper into the intricacies of Web 3 development, let’s explore what it is and why it exists. First of all - what does number 3 mean? The World Wide Web, or Internet in general, has evolved through the years and can be loosely divided into the 3 “generations”:

- Web 1.0 - the first generation, roughly from 1991 to 2004. At this time, the Internet was slow, expensive, and dominated by static web pages. Most people were content consumers, with only a handful of content creators who created and hosted sites. JavaScript was at its infancy, media was rarely seen (due to speed and cost), and social media hadn't been invented yet. The Internet was highly decentralized and open to anyone. Everyone ran their own server or used one of the numerous hosting providers. Open protocols and standards were used for everything - HTTP, HTML, FTP, SMTP.

- Web 2.0 - the current generation, from around 2004 till now. A massive paradigm shift started to happen in the early 2000s. The Internet became faster and cheaper, and slowly but steadily spread into the lives of ordinary people. And as people trickled in, businesses followed. More and more services were offered through the web, like payments, shopping, and deliveries. Pages became more interactive and rich with media, but most importantly - users transitioned from just consuming content, to actively creating one. Social media boomed, smartphones were invented, and the web began its explosive growth we are still seeing to this day. At present day, the Internet touches almost every aspect of modern life, but with all of its usefulness comes a darker side. As it grew, it became more and more centralized. While this centralization brought a number of benefits, there are a number of problems as well. Digital ownership is one of them. As digital assets became ubiquitous, it became apparent that users don't really own them. Instead, ownership remained with centralized companies. Google can block access to your emails on Gmail any time it wants (one example), or a game company can shut down a game server and destroy forever a game you once bought. Another major problem is a loss of privacy. A new business model has emerged, where users “pay” for the services with their personal data. Social platforms ask us to share our personal information so they can feed us information we want to see. Once they have our attention they sell it to anyone who will buy it, effectively harming society for financial gain.

- Web 3.0 - the next generation. It’s still in its early stages, and no one knows for sure how it will evolve, but several key aspects can already be outlined:

- Focus on decentralization and privacy. Shift digital ownership from companies to users.

- Trustless and permissionless.

- Driven by the community through tokenomics and governance.

In this guide we’ll demonstrate some of these Web3 principles in practice and show how to build an application, in which digital assets are decentralized and owned by users.

Building blocks of Web decentralization

As we already briefly discussed, the current Web is highly centralized, and mostly built using client-server architecture on centralized servers hosted on one of the clouds (AWS, Azure, GCP, etc). According to one report, 90% of mobile traffic goes to the clouds, which means a significant portion of the Internet is basically controlled by a handful of companies. This consolidation of power has a number of downsides and this article on "Why Decentralization Matters" does a good job explaining some of those problems.

The first decentralization revolution happened in file sharing, with the arrival of the (in)famous BitTorrent protocol. By being a p2p protocol, it’s truly decentralized, and allows data to be stored distributedly without any central authority (and sometimes without consent of a central authority, which caused a lot of drama, but that’s a story for another time). Ideas behind this protocol have been used in modern decentralized file storages like IPFS and FileCoin, we’ll come back to this later and explore it in more details.

The next revolution happened in the world of finance. For a long time transferring money required a central authority (banks), which would monitor, approve and execute these transfers. This has changed when the first cryptocurrency - Bitcoin - appeared. As already mentioned BitTorrent protocol, it also uses p2p communication, but instead of files it operates a transaction ledger, which is stored as a blockchain. Blockchain structure is needed to ensure that stored ledger cannot be altered, and at the same time to incentivize storage of this data. Unlike BitTorrent, Bitcoin network participants are rewarded for their services using a process called “mining”. This created a foundation for a new form of currency - digital currency (or cryptocurrency), with a unique property that it doesn’t need a central authority to function. Instead, users themselves maintain and operate it. And as with the previous decentralized system, BitTorrent, central authorities have issues with this.

Following the success of Bitcoin, other cryptocurrencies started to appear. The most important one is Ethereum, which took the concept of blockchain one step further and adapted it to store not just a transactions leger, but any kind of data, and, most importantly code (which is just another form of data). Basically, it turned out we can use it as a decentralized database transaction log. And if we have data and code living in the decentralized database, the only thing we lack to build a decentralized application is an ability to execute this code. So Ethereum did just that, and a Smart Contract was born. Now, let's dive deeper into the world of blockchains, smart contracts, and explore how we can build decentralized applications with them.

Blockchain basics

Let's start with a brief overview of what blockchain and smart contracts are.

In classical Web 2.0 applications, you need 2 things to build an application backend: a database to store data and a server to execute your code. The same is true for the Web 3.0, but instead of a database we have a blockchain, and instead of a server we have smart contracts.

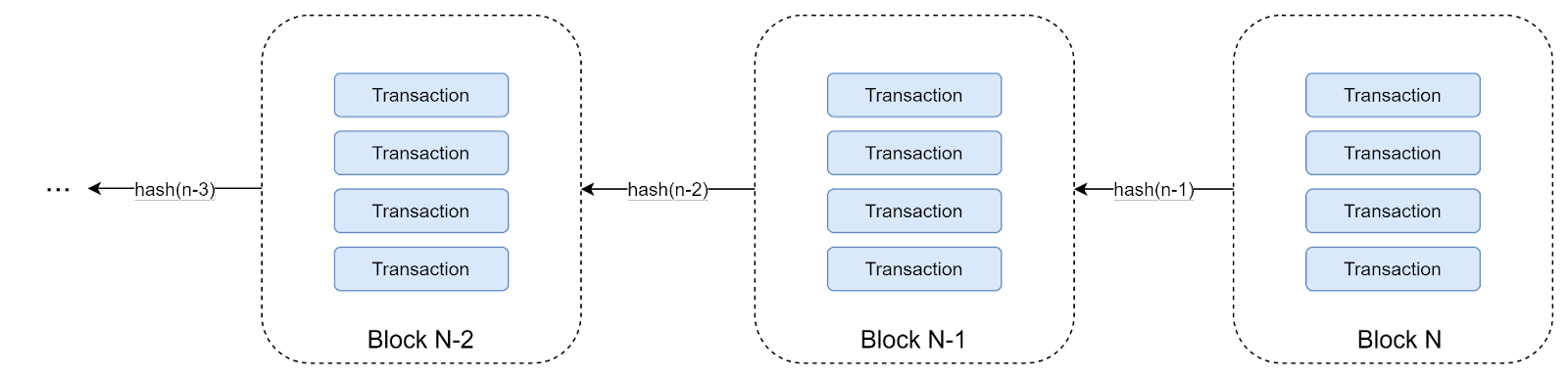

Blockchain itself is just a linked list (chain) of transactions. As a performance optimization, instead of linking individual transactions, they are grouped into blocks. Linking happens using hashes - each block contains the cryptographic hash of a previous block. Such a structure grants us an important property - we cannot modify an individual transaction inside a chain, since it would change its hash and invalidate all transactions after it. This makes it an ideal structure to store in a decentralized fashion, since everyone can quickly verify the integrity of a transaction on a chain (and of the entire chain).

Since we can only add new transactions to the chain, it serves as a decentralized transaction log. And if we have a transaction log, we basically have our database. Another good mental model is to think about this as a decentralized event sourcing pattern, where each transaction represents a separate event.

Due to the distributed nature of a blockchain, that has no single server which would manage a blockchain, a consensus mechanism is used to add new blocks, synchronize data between machines, and incentivize network participation. Several consensus mechanisms exist, we’ll discuss them in more detail later.

It’s important to remember that every transaction on blockchain is publicly visible, so sensitive data should be encrypted beforehand.

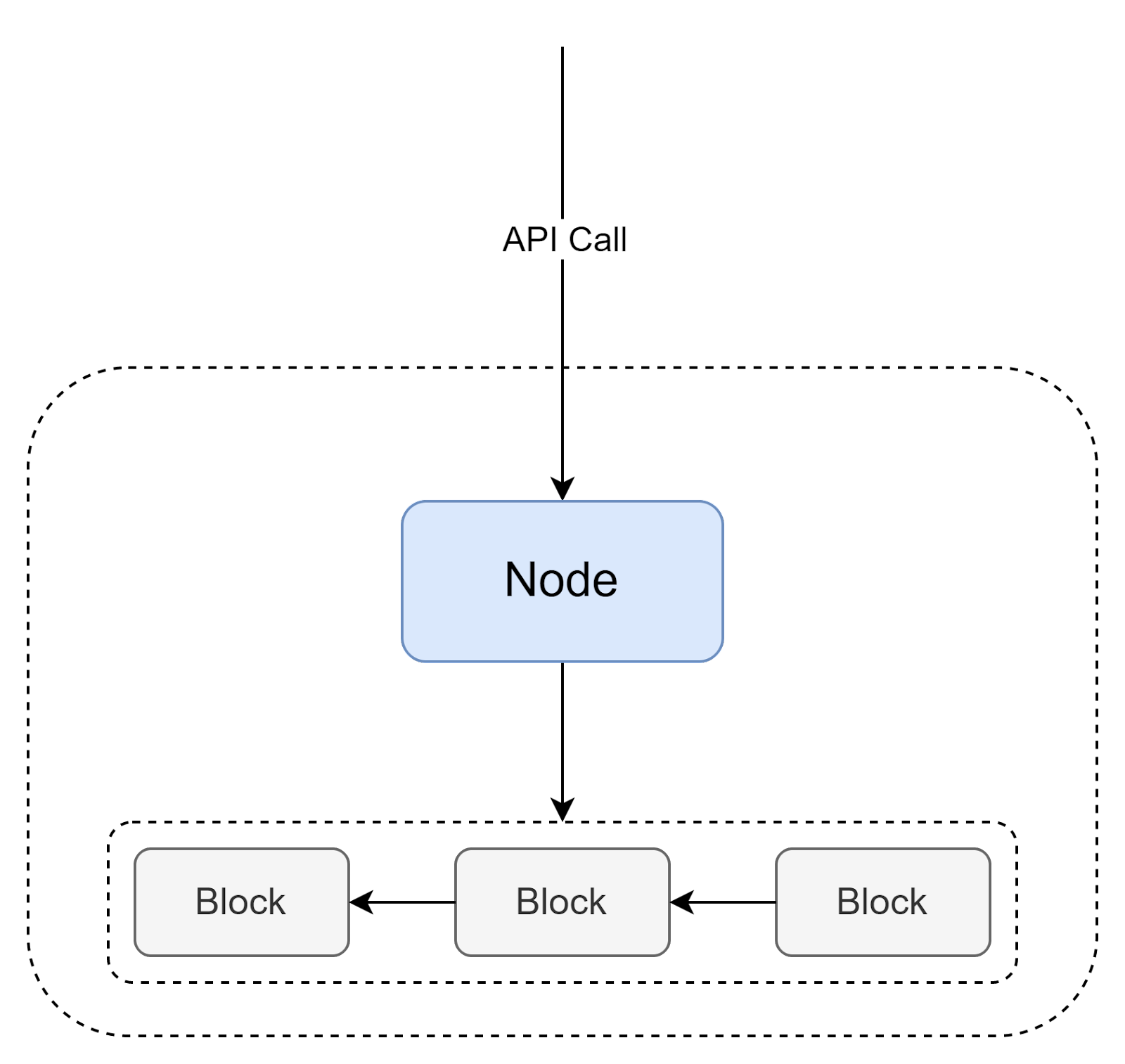

But how do we put transactions into a blockchain? That’s the purpose of a Blockchain Node. Everyone can set up their own node, connect to the p2p blockchain network, and post new transactions. Also, this node provides access to the current blockchain data.

Blockchain transactions themselves can be of a different type; exact supported types depend on a specific blockchain network. In the first Blockchain network, the Bitcoin, which stored only a financial ledger, transactions were quite simple - mostly just transfers of funds between accounts. This works very well for decentralized financing (Bitcoin is still the most popular cryptocurrency), but if we want to build general-purpose decentralized applications (or dApps for short), we need something better. That's where smart contracts come into the stage.

For Web 2.0 developers, a good way to think about a smart contract is as a serverless function which runs on blockchain nodes, instead of a traditional cloud. However, It has a few important properties:

- It is a pure function, which accepts the current state (which is stored on the blockchain) and caller-supplied arguments, and returns a modified state: F(state, args) -> state. In practical terms, it means that we can’t do any external (off-blockchain) calls from it - no API or DB server calls are allowed. The reason behind this is decentralization - different nodes on the network should be able to execute it and get the same result.

- It’s fully open-source. Everyone is able to view your code and check what it’s doing.

- It cannot be changed. Once deployed, code remains on the chain forever and cannot be altered. Different upgrade mechanisms are possible, but are chain-specific.

Such properties allow us to make analogies with real-world legal contracts - they cannot be changed (usually), they're predictable and they're publicly accessible for participants. Smart contracts are basically such contracts, or agreements, but instead of a human performing actions, they are represented as code.

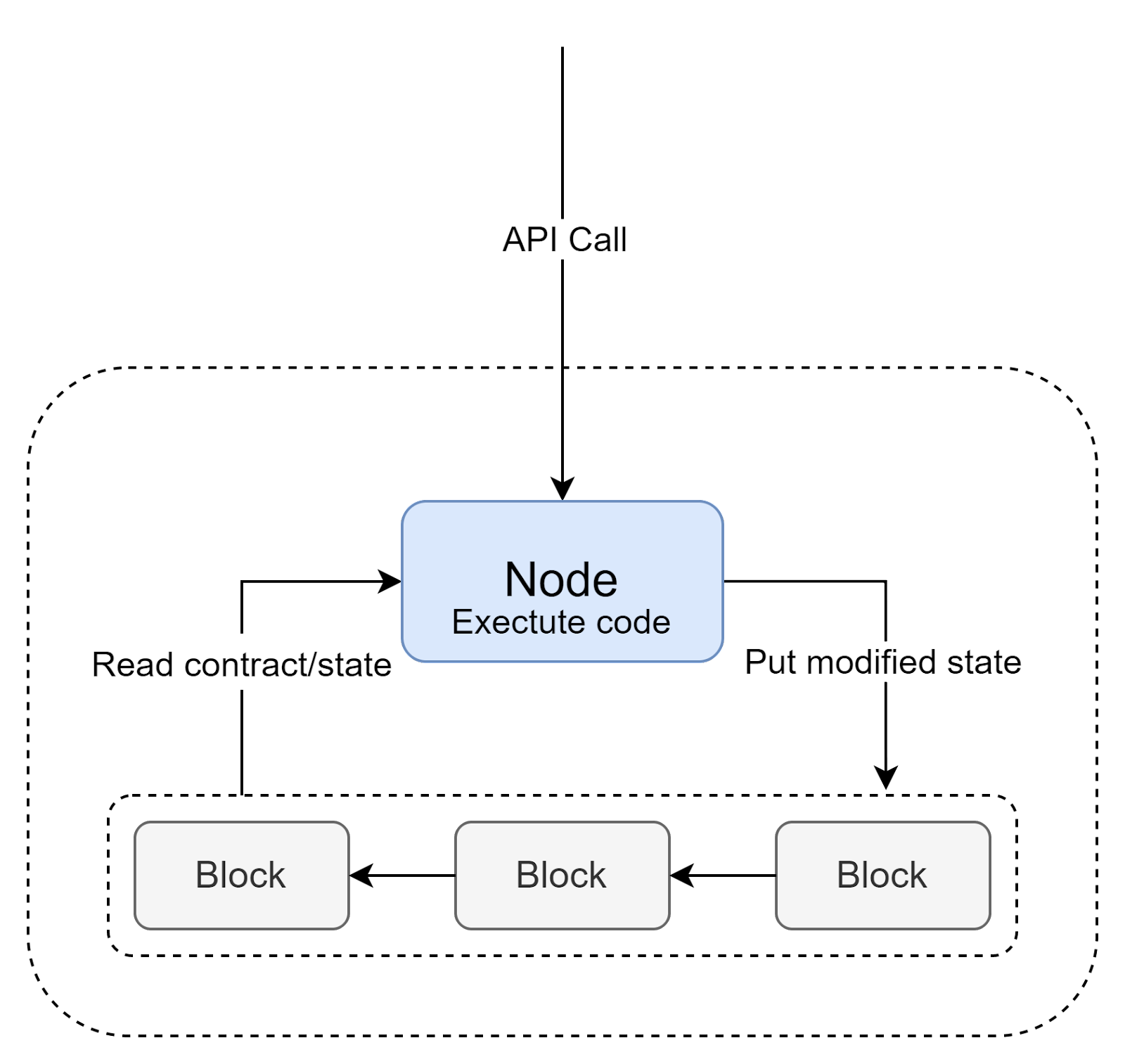

But how do we deploy and execute them, if everything we can do is to create a transaction? All we need are 2 specific types of transactions:

- Deploy smart contract code, so it will be persisted in the blockchain, together with other data.

- Call a smart contract with given arguments. As an outcome, a modified state will be returned.

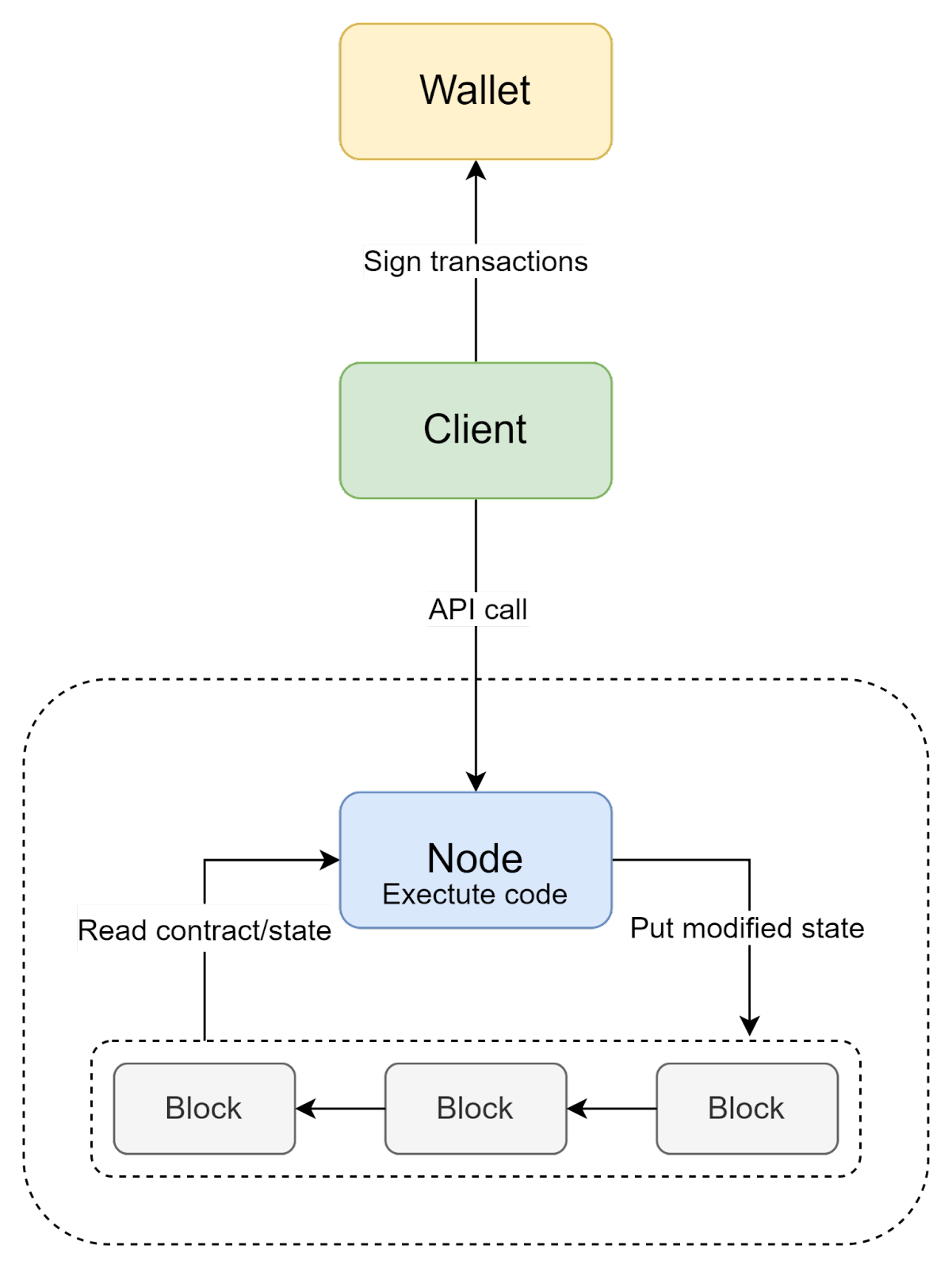

When a call transaction arrives on a node, it will read the contract's code and state from the blockchain, execute it, and put a modified state back on a chain (as a transaction).

So far we’ve explored how the backend layer of a dApp looks like, but what about the client side? Since we are using an API to communicate, we can use any kind of a client we use in the Web 2.0 - web, mobile, desktop, and even other servers. However, an important distinction lies with users.

In a traditional Web 2.0 application, each server owns the identities of its users, and fully in control over who can and can’t use its services. In blockchain, however, there are no such restrictions, and anyone can interact with it (there are private blockchains, but we’ll leave them out of scope).

But how do we perform authentication if there is no standard login/registration process? Instead, we use public key cryptography, where a public key serves as a username, and a private key is a loose equivalent of a password. The major distinction is that instead of a login procedure, in which the server verifies the credentials and grants some form of an access token, here the users sign transactions with a private key. This means there's no classical Web 2 identity (like username, email, or an ID) available. This should be considered if you are building applications that require KYC.

Another important implication of using private/public key pairs for auth, is that they cannot be easily memorized, like username/password pair. For this purpose, special applications called wallets are used. They store user’s key pairs and can sign transactions or provide them for other applications.

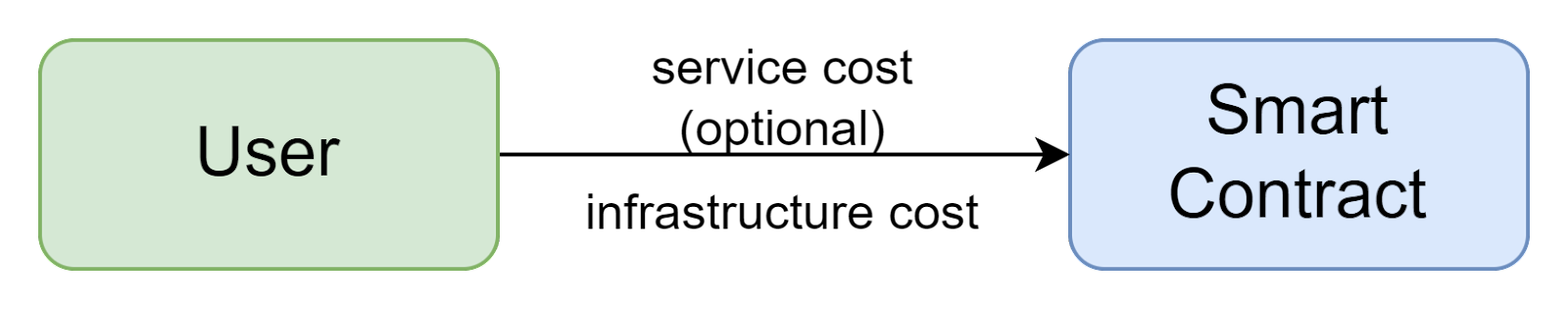

The one aspect we haven’t considered yet is infrastructure cost. In WEB 2.0, users pay for the provided service (directly with money or indirectly with their data, or both), and service providers pay for the infrastructure.

In a Web 3.0 model, users pay directly to the infrastructure provider (nodes running in the blockchain), bypassing the service provider.

This has huge implications:

- Service providers can’t shut down services or restrict their usage, since they are deployed on blockchain and can’t be removed. This means the application will live forever (or at least while the blockchain network is alive).

- A new monetization model should be used for such services, since users don’t pay directly to service providers. For example, a fee can be coded into a smart contract for performing certain actions.

- Since users should pay for the infrastructure, there’s no free lunch (this is usually true for Web 2.0 as well, but it’s often not obvious for ordinary users). Service providers can cover some cost or provide a credit to simplify onboarding, but ultimately users would have to pay.

But how do users pay? Since it’s a blockchain, they can’t pay directly with a credit card - in this way it will be tied to a central authority and not really decentralized. A solution is to use a decentralized currency - cryptocurrency. Each blockchain has its own currency, which is used for payments inside of it.

Whenever a user wants to perform an action on a blockchain by calling a smart contract, it should always pay an infrastructure cost, and optionally a service cost to the service provider.

This infrastructure cost, often called “gas”, usually consists of 2 parts:

- Computational cost - to cover computational power needed to add a transaction into a blockchain.

- Storage cost - to cover additional storage requirements necessary for each transaction.

However, the question still remains how users can obtain cryptocurrency tokens in the first place. One option is to buy it from other users who already own it by using traditional money or another cryptocurrency. There are exchanges which provide such kind of functionality, e.g. Binance. But this will work only if there is already an existing supply of tokens already in circulation.

In order to create and grow this supply the blockchain consensus mechanism is used. Earlier, we mentioned that it is used to incentivize blockchain network participation, but how exactly does it happen? Each node that processes transactions receives a reward for its work:

reward = infrastructureCostReward + coinbaseReward

where:

infrastructureCostReward- share of infrastructure cost paid for the transactions by the userscoinbaseReward- new cryptocurrency token created specifically to reward processing nodes

This means each time a transaction is processed a small amount of cryptocurrency is created, so the amount of cryptocurrency in circulation grows over time (of course some amount of tokens should be created to bootstrap the network, e. g. by using ICO).

At a present day, two consensus mechanisms are commonly used:

- Proof-of-work - original consensus mechanism, which is currently used by Bitcoin and was used by Ethereum. It’s highly criticized for its inefficiency - processing of new transactions requires “mining”, which is a highly computationally intensive process. Because of this, graphic cards became an endangered species. Another disadvantage - cost of transactions is very high and processing speed is also quite slow.

- Proof-of-stake - newer consensus mechanism, which doesn’t require significant processing power (and graphic cards). Processing of transactions is usually called “validation”. Newer chains, like NEAR, use it. Ethereum switched to Proof-of-stake (PoS) mechanism in September 2022. Transactions are usually much cheaper and processing speed is faster.

At this point, we should have enough knowledge to proceed to the next chapter - choosing the best blockchain to build dApps.

Choosing the right blockchain

There are a lot of blockchains out there and it might be hard to choose the most suitable one for your needs. First of all, we should define the most important characteristics for a chain:

- Consensus algorithm - by now Proof-of-work proved to be too inefficient and not suitable for high-scale applications. Proof-of-stake seems like a much better choice for now. Other alternatives exist, but they are less explored and tried in practice.

- Transaction/Storage cost - cheaper cost directly benefits users (recall, that users will pay for it).

- Transaction speed - faster transactions processing time means better user experience.

- Scalability - whether a network is designed to support a large number of transactions. If not, transaction speed/cost may grow out of control over time.

- Development experience - most importantly, what language we’ll use to write our smart contracts. Ethereum popularized Solidity as a programming language of choice for contracts. Several newer chains, like NEAR, chose Rust, which is a more mature general-purpose programming language.

Historically, the first blockchain to introduce smart contracts was Ethereum. However, as the number of users grew, transaction speed and cost skyrocketed, and it became apparent that it couldn't handle the demand. So, a number of scaling solutions appeared - layer 2 chains, sidechains, and plasma chains. However, they all use some kind of workarounds with their own unique drawbacks. Ethereum tries to fix the core problem and redesign its network - like switching to a Proof-of-stake consensus, which is ongoing for quite a long time, but exact timeline when all of the problems will be fixed is very unclear.

Meanwhile, a new generation of blockchains started to appear. They learned from the Ethereum mistakes, and designed them from ground-up to be fast, cheap and scalable. Choosing the right one is by no means an easy task, but for us we found the NEAR blockchain to be an ideal solution, because of the following properties:

- Transactions are cheap and very fast.

- Designed to be extremely scalable from the beginning. This means we can count that transaction cost and speed will remain stable in the future.

- Uses Proof-of-stake consensus mechanism - so no hated “mining” is needed.

- Rust is used as a primary programming language. Since it’s a popular language (and one of the most loved), it’s much easier to learn and find developers on the market.

All of the further sections will use NEAR as an underlying blockchain, so before we jump into the intricacies of the Web 3.0 migration, we should take a closer look at it first.